Why you probably shouldn't raise VC money for your SaaS business (and when you should)

Do you really want to get on the "outside capital hamster wheel"? + decision tree to help you decide if you should raise from VC.

👋 Hi there, I’m Justin. Welcome to another edition of SaaS Decoded. Each week, I publish an in depth, actionable guide to help SaaS founders and operators grow their businesses.

I still remember the moment like it was yesterday.

I was sitting in one of the last lectures of my business administration degree half listening, half in deep thought.

I was running through a problem I had stumbled across a few weeks earlier. Then it hit me… I had worked out the solution.

I almost jumped out of my seat in excitement and immediately knew that the next phase of my life would involve building a tech startup.

I spent the next two and a half years working on Bmark, a “smart” bookmarking and sharing solution.

To say Bmark went no where would be an understatement.

I made so many mistakes, went into debt and burnt a lot of time.

I learnt a lot but no where near what I could have if I spent that time working for the right company. Opportunity costs are real and usually higher than we like to admit.

The idea of building a large, world-changing tech startup is very romanticized.

We all know the names behind the great success stories but you almost never hear the stories of the tens of thousands of entrepreneurs that took a shot and failed.

When I think back on this period I wish I was a bit more grounded and understood what it really takes to build a “unicorn” (a business with a billion dollar valuation).

I also wish I understood back then that there are many ways to play the game of business, and perhaps trying to big a large tech business backed with VC money wasn’t the best route for me.

This post is the guide I wish I had back when I first sat down to start building Bmark.

My hope is that this guide will help you think through the best path for your business and save some of you years of regret.

This post will cover the following topics in detail:

Do you really want to play the “VC-backed tech startup” game?

Is my startup what VCs are looking for?

Should I raise VC money for my tech startup?

The three most important lessons I learnt failing to raise VC money

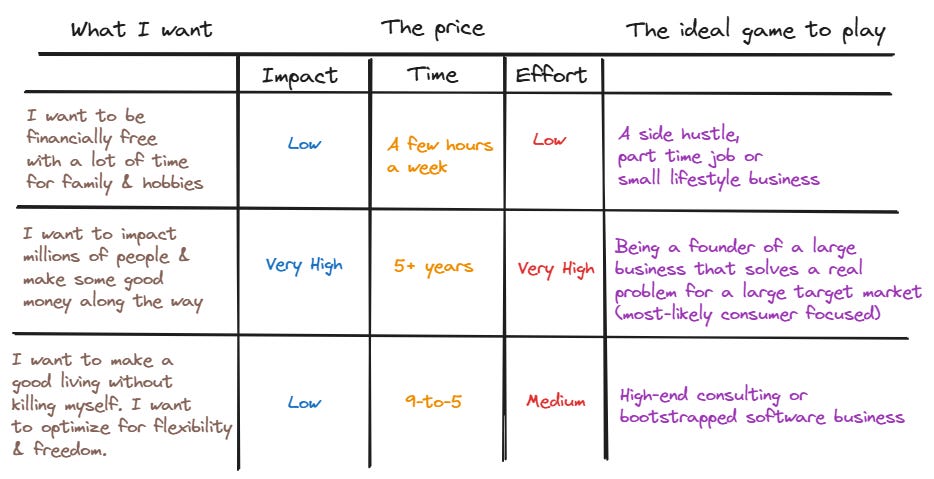

It should start with what you want

Do you want to be financial independent, change the world, live a comfortable life while working a minimal number of hours, or be filthy rich as quickly as possible?

There are many different games you can play when it comes to business but before you choose “your game”, it’s important that the game aligns with how you want to play it.

There are a few key variables that you have to take into account.

“Impact” would be the first one on my list.

This would be the impact your business will have on the world.

There is a reason Jeff Bezoz and Mark Zuckerberg are super wealthy. Their businesses changed the world and have impacted billions of people.

That chrome extension you’re building that will help accountants save ten minutes a month updating their Google sheets is on the other end of the spectrum.

For the most part the richest people in the world have provided a disproportionate amount of value to the world.

The next variable to consider is “effort”.

If what you really want is to lead a balanced life with plenty of time for hobbies, relaxation, socializing and adventure then certain ways of playing the business game isn’t for you.

If you really want to change the world by tackling a really difficult problem, or set of problems, then it might just take everything you have in order to succeed.

Time is the next variable on the list.

Let’s assume for a second your goal is to build a billion dollar software business.

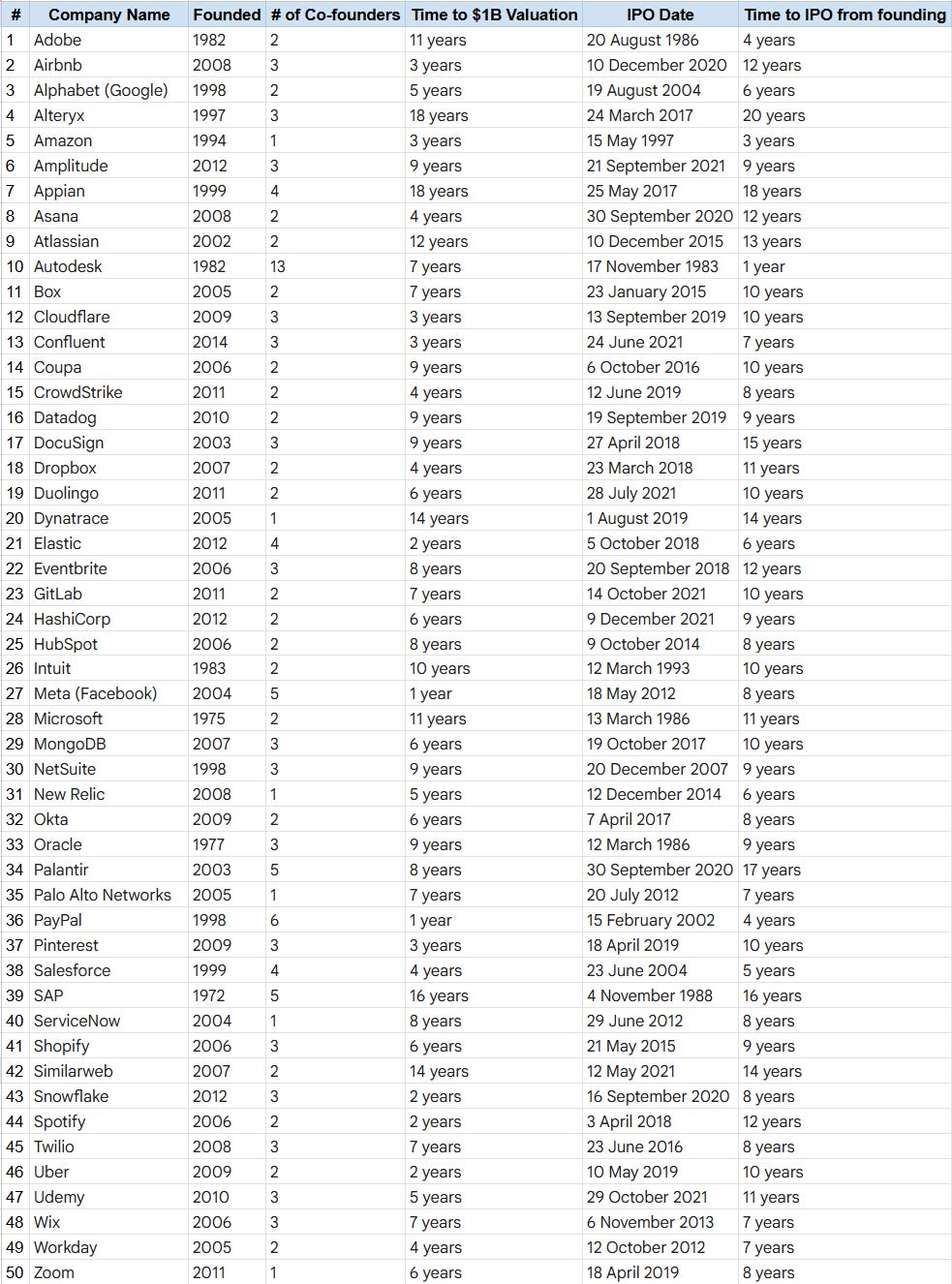

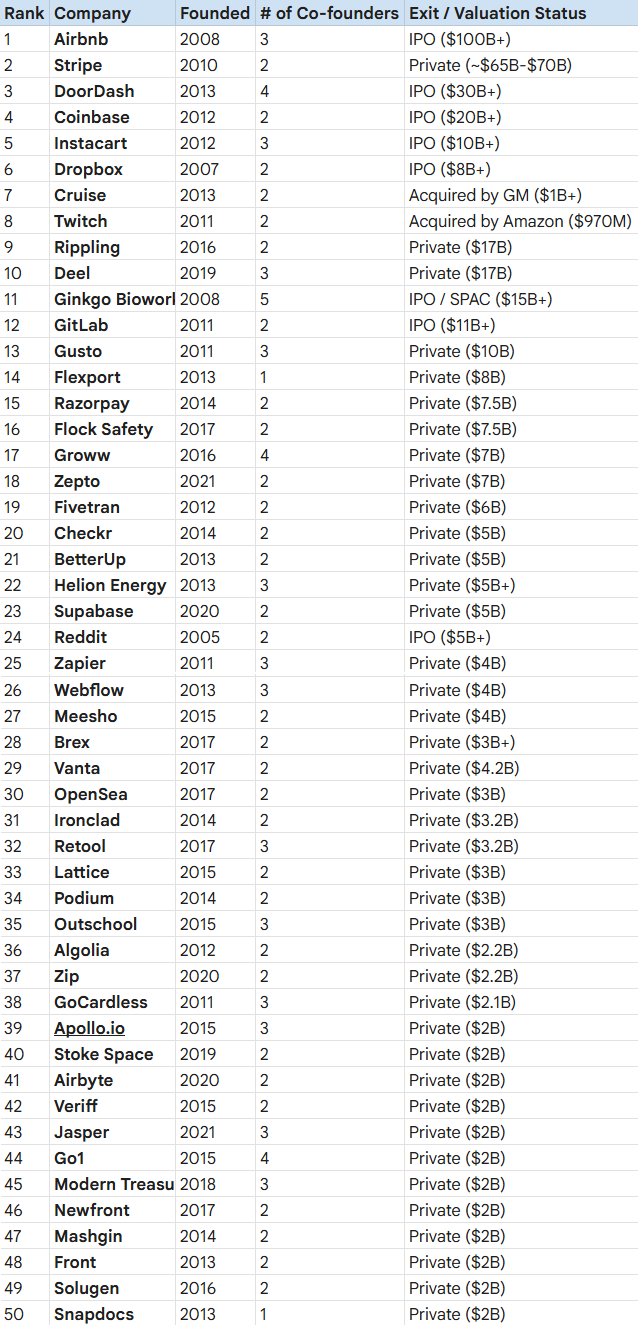

How long, in years, do you expect you’ll need to work to reach that goal? Well luckily we have some data we can use to answer this question.

Above is a table of 50 well-known, publicly traded software businesses.

Here are some interesting insights from this list:

The median time to a $1 billion dollar valuation from founding is 6 years. The 80th percentile is 9 years. The max is 18 years!

The median time to IPO from founding is 9 years. The 80th percentile is 12 years. The max is 20 years!

Atlassian, the makers of Jira, one of the most well-known software products in the world took 12 years to reach a billion dollar valuation. Even the almight Google took 5 years to hit the milestone.

Most people lack patience and aren’t willing to dedicate years towards a single mission.

Once you’ve understood these key variables and decided where on the spectrums you land, you can decide which game you want to play.

Just remember, most people lose because they aren’t willing to pay the price it takes to win.

Should I raise VC money for my tech startup?

As a software founder you have 3 choices when it comes to choosing how to scale your business.

Option #1 - Bootstrap

Option #2 - Raise capital from venture capitalists

Option #3 - Raise capital from other sources

Option #1 - Bootstrap

To bootstrap the business means to grow the business using revenue generated by the business.

The founder or founders will cover the operating costs of the business until the business breaks even and then use the revenues generated to invest back into the business.

The initial money will usually come from savings, or by the founders working at some capacity until they can go full-time on the startup.

The benefits of this approach are:

Keep complete control of the business.

No pressure to grow the business at all costs.

No need to raise additional rounds of funding every 12 - 36 months.

No long term valuation-based goals makes the business suitable as a “lifestyle” business.

Can optimize for higher profits since growth isn’t necessarily the main focus.

The downsides of this approach are:

Slower growth compared to the option of raising outside capital.

More risk since competitors could raise funding and outpace your product development and start capturing your marketshare.

Having VC money could help you survive financial downturns or other unforseen influences. Without having the protection of cash in the bank, there is a higher risk that the business goes under.

Option #2 - Raise capital from venture capitalists

The second option is to raise capital from venture capitalists (VCs for short).

To go this route requires giving up equity in the business (ownership) in exchange for cash.

This cash is then used to hire employees and grow the business at a significantly faster pace than would be possible if the business decided to bootstrap.

This opproach is the only opproach for founders that are playing a “winner takes all” game.

Good examples of such businesses would be Facebook, Uber and Airbnb. These three businesses are essentially monopolies but needed significant capital to get to that point.

The benefits of this approach are:

If you’re playing a “winner takes all” game, raising significant capital from VCs will give you a fighting chance.

Allow you to hire a team and accelerate growth far quicker than if you bootstrapped the business. It allows the business to grow while being unprofitable.

Raising VC money gives you the opportunity to get some press which can help with growth and hiring.

The right VCs can become long-term partners and mentors that will increase your chances of long-term success.

It allows the option of a “secondary” round for the founders. This means the founders can take some money “off the table” in exchange for selling their equity.

The downsides of this approach are:

You will have to give up equity in your company and in most cases set up a board of directors (most VCs will want one or more board seats in addition to equity). This adds complexity and overhead.

Once you go the VC route, it usually means needing to raise multiple rounds of funding until the company goes public. This means more dilution of ownership of the founders, an increasingly more complex cap table, and more overhead for the CEO and CFO.

There is no guarantee you will be able to raise a round of funding when needed which will lead to major layoffs, or even the business having to shut down. Being bootstrapped forces more financial discipline.

Option #3 - Raise capital from other sources

VCs aren’t the only source of capital for startups.

Friends, family and angel investors are commonly used to raise the first round of capital (the “seed” round).

Banks and even the government can also provide capital to startups, however this route is a lot less common.

Some accelerator programs provide some seed funding to participants in their programs.

Y Combinator is the most well-known accelerator in the world. Y Combinator invests $500,000 in startups accepted into their program. In return the accelerator gets 7% of equity.

Is my startup suitable for VCs?

A question a lot of inexperienced founders forget to ask themselves is if their startup is suitable for VCs.

VCs are playing their own game and its critical that founders understand it before trying to raise money from them.

VCs raise money from principles, form a fund and invest in companies. The expectation is that within 8 - 12 years the VC returns the money (and some profit) to their investors.

For every 10 bets that VCs make, most will go to zero, 1 or 2 will have a small “exit” (1 - 5X return), and 1 will have a large exit (50X+ return).

That single large exit could return the entire fund and is the holy grail for VCs. For more on VC math, check out this useful article.

Since the math is so scewed towards these large exits, VCs won’t make bets that don’t have the potential to have huge exits.

Let’s say your startup is a CRM system designed specifically for pet store operators. You decide to target the US market and based on preliminary market research you can charge the average customer $50 a month for your solution.

A quick Google search will tell you that there are roughly 18,000 pet stores in the USA (in 2025). Assuming you can get 100% market share, you can expect your US business to generate $10,800,000 in revenue a year. This assumes zero churn.

A VC would never take a bet on such a business because the potential upside is simply too small.

A business like the one I described above would be great for a solo operator who could run it on the side while working a full-time job, or simply operate it as a high-margin lifestyle business.

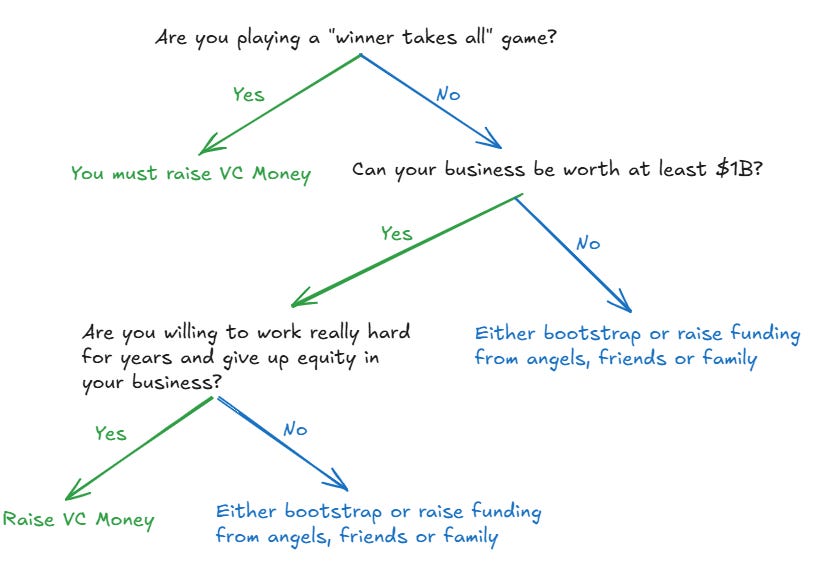

Now that we’ve covered the three main ways a tech startup can grow, and what kind of businesses VCs are interested in, let’s answer the question, “Should I raise VC money for my tech startup?”

The decision tree below should help you get to your decision.

The three most important lessons I learnt from failing to raise VC money

During the 2.5 years working on Bmark I approached over 70 angel investors and VCs and failed to raise any funding.

Anyone who has tried to raise funding for a startup will tell you how tough it is.

Jeff Bezoz famously said that raising the seed round for Amazon was “the hardest thing I’ve ever done”.

From all the rejection I experienced trying to raise a seed round for Bmark, I managed to learn three important lessons.

Lesson #1 - Risk is an important factor for VCs and shouldn’t be ignored by founders

VCs see thousands of opportunities every year but can only make a few bets per fund.

One of the most important factors that go into VCs calculus is risk.

When I was trying to raise funding for Bmark I was a solo founder with no prior startup experience. I had no traction, a half backed product and no revenue.

To say Bmark was a risky bet would be the understatement of the year.

As a startup founder, it’s your job to acknowledge the risk factors in your business and work hard to mitigate them.

Showing potential VCs that you are capable of hitting milestones, building a product loved by users around the world, and generating revenue helps to lower risk.

Lesson #2 - VCs prefer startups with multiple founders

Let’s look again at the list of 50 publicly traded tech companies.

If you look closely you’ll notice only 6 of the 50 (12%) have a solo founder, the most notible being Amazon.

As I previously mentioned, it takes many years to get a tech company to a $1B valuation and even longer to an exit. There are a lot of ups and downs during this time and it can be very tough for a solo founder.

To help lower the risk, VCs prefer to invest in startups with multiple founders.

VCs aren’t the only ones who prefer to invest in multi-founder startups.

The table below shows the top 50 Y Combinator startups ranked by exit amount or estimated valuation. Only 2 in the list have a solo founder.

So what does this mean for you as a solo startup founder? The data is clear but I think it is a very personal decision and it comes down to what you want and how you play with others.

Lesson #3 - Raise a pre-seed from angels, then go after VCs

If you have decided to raise capital for your startup, you’ll find it far easier to raise your initial investment from angel investors instead of VCs.

This is especially true if you decide to raise a relatively small seed round (<$1M). You could even call it a “pre-seed” round.

You could then use that capital to launch your product, gain some traction, and maybe even generate some revenue.

This will help lower perceived risk in the business and better position you to raise a significant round of funding in your next round from VCs.

I’m a fan of this approach since it allows the founder/s to move the business forward, experience having capital to work with, and operate with some financial constraints (since it’s only a small pre-seed round).

The business gets a taste for the “outside capital hamster wheel” without having to spend 6 - 12 months chasing VC money (raising VC money is typically a 3 - 9 month process).

A lot has changed in the VC space in the last ten years and there are far more funds interested in investing in seed rounds of far riskier startups. I would target these VCs along with any relevant angels for your “pre-seed” round.

Thanks for reading and have a great week.

Justin

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already.